Ratings reveal the real value of Indonesia’s nature-based solutions

Here are some key takeaways

Indonesia contains vast carbon reserves across its forests and peatlands. Preserving these ecosystems is vital for effective climate change mitigation.

Despite the potential for high quality credits, projects risk subdued demand if they fall short of international standards and thresholds.

Carbon ratings can enable high integrity Indonesian projects to attract funding and demand.

Introduction

Indonesia is at a critical juncture from which it could emerge as a world leader in climate mitigation. The country is one of the world’s largest carbon sinks, home to the third-largest tropical rainforest and nearly a third of the world's tropical peatlands, ecosystems that store vast amounts of carbon. Yet paradoxically, it also ranks among the world’s top 10 emitters. As such, Indonesia faces a formidable challenge: decarbonising its fast-growing economy.

The opportunity, however, is equally immense - to safeguard and restore its natural assets while setting the standard for sustainable growth.

Although such ecosystems hold significant value, conserving forests comes at a significant cost. The Energy Transitions Commission estimates that it would require more than USD 130 billion per year to protect all forests at high risk of deforestation.¹ The uncomfortable truth is that in almost all instances, clearing forests for agriculture or industry is more profitable than keeping them standing.

This rings true for Indonesia, where commodity-driven deforestation has already converted more than a third of the nation’s primary forest into oil palm and acacia plantations.² In the face of high opportunity costs, declining levels of philanthropic aid, and a global agenda focused on economic growth, carbon finance presents a potential solution.

How regulation reshaped Indonesia’s carbon credit supply

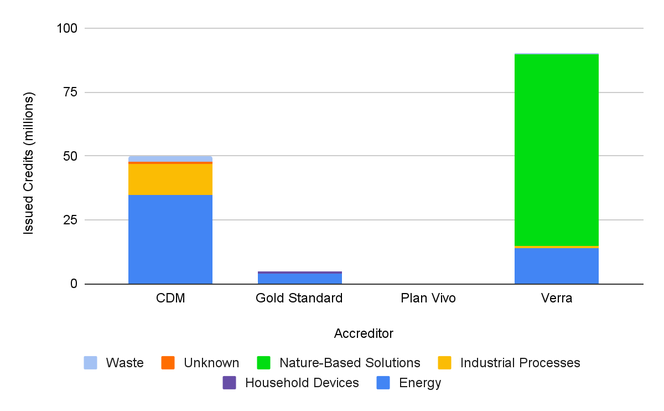

To date, Indonesia has issued approximately 145 million credits across major registries, including Verra, Gold Standard, and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Roughly half of these credits were generated by peatland projects, which in turn equate to 1.5% of total global issuance.

Figure 1. Issued credits from Indonesia under four major standards as of September 2025.

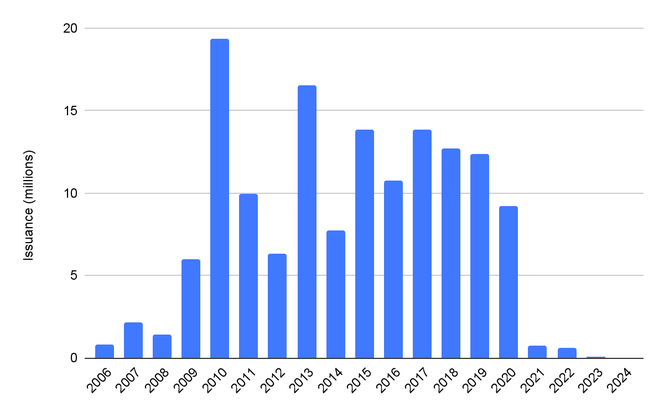

In 2021, Indonesia issued a moratorium on the export of credits. This enabled the country to take the time to implement regulations and domestic infrastructure that help to govern its carbon projects before reopening to international markets.

This includes developing a national registry (SRN-PPI), on which all projects must be listed; establishing the IDXCarbon exchange, through which all trading must take place; and resuming the international sale of carbon credits, ensuring that domestic rules and standards are still upheld.

In addition, Indonesia has signed mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) with major standards bodies, including Verra, Gold Standard, and Plan Vivo. Under the MRA, projects can be certified under partner standards, subject to compliance with Indonesian law and the Ministry of Environment's approval process. These agreements provide investors with a familiar governing framework and help to make the market more internationally accessible.

Whilst these efforts have undoubtedly strengthened the oversight of domestic carbon projects, they have also stalled international financing flows that support conservation measures and low-carbon development. Although internal administration has improved, there is still a need to enhance transparency surrounding domestic standards, project reporting, and regulatory frameworks to attract external investment.

Figure 2. Indonesian issuances fell sharply after the international moratorium on the export of credits.

Carbon ratings offer an independent assessment of quality

Carbon ratings offer an independent measure of credit quality that can be applied consistently across markets. They move beyond broad, top-down assessments by capturing project-specific details and presenting them in a clear, comparable format.

The BeZero Carbon Rating uses an eight-point scale from ‘AAA’ to ‘D’ to indicate the likelihood that a carbon credit represents a tonne of CO₂e that a project has avoided or removed for its full commitment period. All ratings incorporate three key risk factors: additionality, carbon accounting, and permanence.

Indonesian NBS projects are among the highest-rated globally

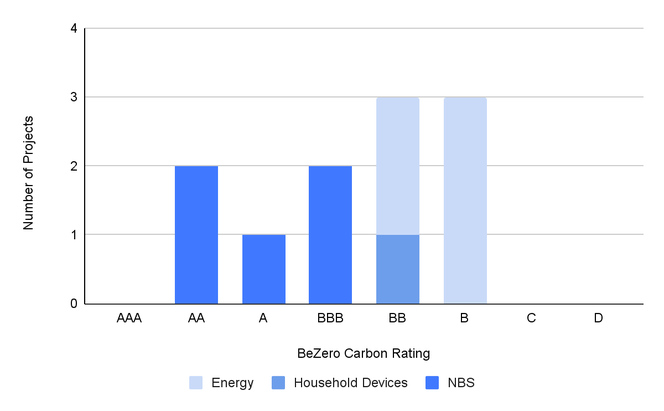

To date, we have rated 11 ex post projects in Indonesia, with ratings ranging from ‘AA’ (very high likelihood) to ‘B’ (low likelihood). The average rating we have awarded to nature-based solutions (NBS) projects in Indonesia is a ‘A’; this represents a high likelihood of credits achieving one tonne of CO₂e avoided or removed. In comparison, the most common NBS rating across other countries is a ‘B’.

Figure 3. BeZero Ratings of Indonesia-based projects. Of the 11 ex post ratings to date (October 2025), the sub-sectors covered are Peatlands, Mangroves, Clean Water, Wind, Hydro, and Geothermal.

The three REDD+ projects in this portfolio are all identified by us as Avoided Planned Deforestation (APD) and peatland conservation. Of the 62 Avoided Deforestation and Peatland projects we have rated globally, the most common rating is ‘BB’. This suggests that Indonesia could host some of the highest-quality carbon credits in the market.

Some of the drivers of higher-quality Indonesian REDD+ projects include:

High additionality of projects: In Indonesia, there are very real threats of land conversion. By some estimates, approximately 2.4 million hectares of intact forest and peatland remain within Indonesia’s oil palm concessions.³ This leads to high opportunity costs for conservation, which, given the absence of alternative financial incentives for protection, suggests that carbon finance is essential for the NBS projects we have rated.

Robust carbon accounting: We have observed best-practice carbon accounting in the rated Indonesian projects, given the use of conservative baselines, robust field measurements (e.g., extensive peat core sampling, permanent sample plots, and satellite monitoring), and the application of uncertainty discounts. Although leakage potential remains significant, displacement may occur on less carbon-dense landscapes, and issuance deductions can be made to account for residual risk.

Higher likelihood of permanent impact: Project longevity is generally supported by secure long-term land tenure through legal mechanisms, such as ecosystem restoration concession licences. The projects we have rated also provide substantial buffer pool contributions (often exceeding minimum requirements) and enact active risk mitigation measures, such as canal blocking, fire monitoring, and community engagement.

Additional impacts beyond carbon: The projects have implemented a variety of measures to benefit local stakeholders and the wider environment. Some initiatives cover community conservation and benefit-sharing agreements, as well as dedicating significant funding to social and economic development. In particular, given the rising number of endangered species in Indonesia, these NBS projects offer vital strongholds for at-risk wildlife.

Despite their quality, these projects risk being excluded from critical markets, potentially foregoing associated price premiums and buyer demand.

Quality projects are at risk of being excluded from international markets

Article 6

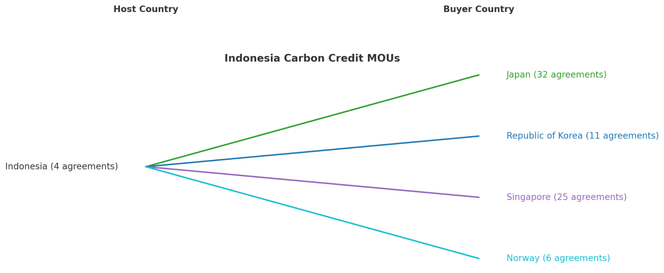

Credits trading under Article 6.2, the bilateral country-country market for credits, appear to fetch a price premium. Indonesia has already entered into memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Norway. Eligibility lists have yet to be finalised under these MOUs, but based on the available information, no nature-based methodologies have been approved from Indonesia for Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM).⁶ In addition, published whitelists between Singapore and other countries suggest that the eligibility criteria will mirror that of CORSIA (discussed below), potentially reproducing similar restrictions for Indonesian REDD+ and peatland projects aiming to access Article 6.⁷

Figure 4. Current memorandums of understanding in place with Indonesia under Article 6.2.

Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism aims to create a formal market; however, there is a risk that nature-based projects could be rejected from this scheme. The latest draft of the market design would require activities to demonstrate a ‘negligible risk of reversal’ (defined as a very small percentage loss over 100 years), recommending a single threshold in the range of 0.5 – 2.5%. Discussions surrounding this are ongoing, but should these conditions be accepted, land-based nature projects are at risk of exclusion due to the practical difficulties of monitoring over this time horizon and the inherent reversal risks faced by all such projects.

CORSIA

The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) is one of the largest compliance markets, requiring airlines from over 120 participating countries to offset their emissions growth. Demand under this scheme is expected to exceed 1.7 billion tonnes over Phases 1 and 2; however, so far, only a few million credits have been made available to the market, all of which are from Guyana’s Jurisdictional REDD+ programme.⁴

There are significant barriers to Indonesian projects accessing the CORSIA market.

To be eligible for CORSIA Phase 1, REDD+ projects must either generate fewer than 7,000 tCO₂e per annum or be registered under the Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART) or Verra’s JNR framework and have corresponding adjustments and host country Letters of Authorisation. At present, these requirements exclude all Indonesian REDD+ projects. Meanwhile, the only eligible peatland activity is the rewetting of temperate peatlands, which naturally excludes Indonesia’s tropical systems.

Indonesia’s REDD+ and peatland portfolio is dominated by project-level activities that typically far exceed the CORSIA emission threshold. Emissions from drained peatland, for example, have been estimated at up to 178 tCO₂e per hectare.⁵ As such, virtually all commercially relevant projects would fail to meet the ‘small-scale’ criteria.

In principle, such projects could qualify under CORSIA if Indonesia establishes a registered jurisdictional programme and reference level, enabling project nesting and authorisation under Article 6. However, this pathway involves substantial technical, political, and administrative challenges.

For example, APD projects would require reconciliation of legal conversion rights, land-use concessions, and national policy. In addition, APD can also be tied to legal deforestation rights, so governments may be reluctant to formally recognise these. Peatland inclusion introduces further complexity, such as accounting for hydrology, fire, and emission factors, data which are rarely complete at the national scale.

Core Carbon Principles

Other market labels and buyer preferences that can attract price premiums are the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market’s Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and, more generally, removals-based credits, the latter of which necessarily exclude the bulk of REDD+ and peatland conservation activities.

Similar to CORSIA, jurisdictional-level REDD+ activities registered under ART or Verra’s JNR framework have been CCP-approved, while project-level methodologies are limited to ACR’s USA-based protocol and Verra’s VM0048. Currently, no peatland rewetting or conservation methodologies have a CCP label.

Although all REDD+ projects under Verra will be required to transition to the VM0048 methodology, this framework is only operational for Avoided Unplanned Deforestation (AUD) projects. The APD and peatland modules are still under development, while Verra’s jurisdictional risk maps are being rolled out progressively; however, Indonesia has not yet published final compliant data. APD and peatland projects, therefore, lack both the methodological framework and the jurisdictional data necessary to utilise VM0048 today.

The reasons underlying market eligibility criteria

There are several reasons underlying the eligibility criteria of the aforementioned markets and labels.

Over-crediting risk: Concerns exist regarding the baseline setting of project-level REDD+ and avoidance credits more generally. There is a perception that shifts to jurisdictional-level crediting will mitigate these risks, whilst there is more confidence in the zero baseline of removals credits.

Lack of data: There is a lack of established data specifically related to tropical peatlands, and less certainty in monitoring results.

Permanence risk: This relates to both REDD+ and peatland projects, particularly given the flammable nature of peatlands and their vulnerability to changing climates.

These are all valid concerns from a top-down perspective, but our analysis of Indonesian projects reveals that this is not the full picture.

APD risk mitigation: APD projects generally carry lower over-crediting and permanence risk than other NBS because their baselines are anchored in documented, legally sanctioned conversion plans rather than modelled diffuse pressures. This increases confidence that the ‘without-project’ emissions would have occurred. Permanence also tends to be stronger as they typically operate in areas with clear land rights and enforceable controls, allowing binding agreements such as easements that reduce the likelihood of reversals.

Peatland risk mitigation: For tropical peatlands, even where national data are incomplete, most methodologies apply conservative assumptions that suppress credit volumes and thereby reduce over-crediting risk. Permanence is also often better characterised because emissions are driven largely by the hydrological state. Maintaining high water tables and fire management are discrete, monitorable interventions that materially lower reversal risk relative to landscapes dominated by diffuse, hard-to-control drivers of unplanned deforestation.

Avoidance credit risk mitigation: While avoidance projects typically involve greater uncertainty than removals due to the counterfactual baseline, their exclusion from these schemes carries a disproportionate risk. If the baseline scenario materialises (e.g., deforestation proceeds), there will be a negative environmental outcome, with both forest loss and associated emissions. In contrast, the non-existence of removal projects does not necessarily influence environmental outcomes, since no new sequestration occurs, but no additional emissions are caused.

The case for ratings

By falling short of market requirements and quality labels, Indonesian NBS avoidance credits risk being undervalued and overlooked. Ratings can be a useful tool to help bridge this gap and restore buyer confidence, rather than writing off critical credit supply.

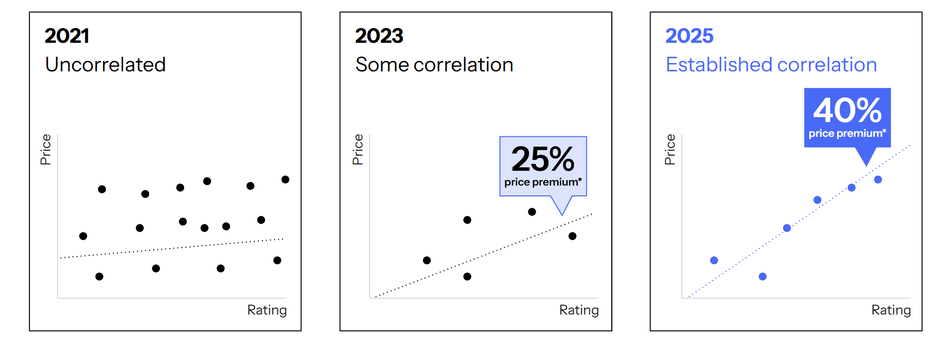

Since BeZero began publishing ratings a correlation has emerged between credit prices and credit quality. According to data from Fastmarkets, project-type carbon price assessments based on our ratings reveal approximately 40% price increases between each rating band.⁸ Notably, a peatlands project in Indonesia saw its credit prices nearly double after receiving a one-band rating upgrade from an ‘A’ to a ‘AA’ in February 2025.

Figure 5. The established correlation between BeZero Carbon ratings and credit prices. *Average price difference between credits separated by one BeZero rating notch. Median price and price interquartile range (indicated by range bars) by BeZero Carbon Rating at the time of transaction, for transactions undertaken in 2024 (up to end of November). Transacted prices from Xpansiv CBL exchange.

There is an increasing convergence between compliance and voluntary markets that is crucial to creating a harmonised market with common principles. While the international frameworks governing these are essential, ratings provide a complementary tool that is needed to integrate independent project-level risk assessments.

Should Indonesian REDD+ or peatland projects eventually be deemed eligible under certain compliance schemes, they could still benefit from independent ratings that enhance transparency, facilitate price discovery, and foster investor confidence. For example, governments from Singapore to Switzerland are using ratings to navigate fragmented market frameworks. Whether projects are included, excluded, or caught in regulatory limbo, ratings provide an independent signal of quality that helps ensure high-integrity Indonesian credits are recognised – regardless of shifting market rules.

Conclusion

Indonesia sits at a crossroads. Despite being home to some of the highest-quality nature-based projects globally, regulatory uncertainty, high domestic abatement costs, and restrictive eligibility criteria in compliance markets have depressed prices and deterred investment. With carbon credits currently trading at a fraction of the real cost of abatement, and key project types like REDD+ and peatland conservation facing exclusion under evolving international rules, Indonesia’s most valuable assets risk being systemically undervalued and overlooked.

For buyers and sellers alike, this creates both a challenge and an opportunity. Independent ratings provide a clear, comparable measure of integrity across fragmented markets, enabling buyers to identify high-quality supplies that may be mispriced due to regulatory or perception gaps. By providing transparent, project-level risk assessments, ratings help de-risk capital allocation, improve price discovery, and enable investors to capture upside as the market corrects. In this way, ratings are not just a risk assessment tool - they are a lever to unlock value, drive liquidity, and channel investment into projects with both robust climate impact and strong return potential.

Ultimately, in the face of accelerating climate change, Indonesia is too significant to overlook. Ratings are critical to ensuring its natural assets receive the recognition and value they deserve.

References

Energy Transitions Commission Financing the transition: The costs of avoiding deforestation. Available at: https://www.energy-transitions.org/financing-the-transition-the-costs-of-avoiding-deforestation/

Spracklen, D.V., Arnold, S.R., Wooster, M.J., Rossi, V., Sullivan, M.J.P., Malhi, Y., Roe, J., Silverio, D.V., Aldrich, M. and Crouzeilles, R. (2024) ‘The costs of halting tropical deforestation’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(10), e2318029121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2318029121.

Benedict, J., & Heilmayr, R. (2024). Indonesian palm oil exports and deforestation. Trase. https://doi.org/10.48650/0ZP9-GH11

Fastmarkets (2024) Demand tailwinds meet supply headwinds: Forecasting CORSIA’s impact on carbon credit markets. Available at: https://www.fastmarkets.com/insights/demand-tailwinds-meet-supply-headwinds-forecasting-corsias-impact-on-carbon-credit-markets/

Hooijer, A. et al. Subsidence and carbon loss in drained tropical peatlands. Biogeosciences 9, 1053–1071 (2012).

Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) Indonesia–Japan (n.d.) Approved methodologies. Available at: https://www.jcm.go.jp/id-jp/methodologies/approved

Singapore’s Carbon Markets Cooperation (n.d.) Overall Eligibility List. Available at: https://www.carbonmarkets-cooperation.gov.sg/environmental-integrity/overall-eligibility-list/

Fastmarkets (2025) Carbon credit ratings and market news: Price trends and anomalies. Available at: https://www.fastmarkets.com/insights/carbon-credit-ratings-and-market-news-price-trends-and-anomalies/